During the Covid-19 epidemic, it became necessary to carry valid photo ID to certify an individual’s possession of vaccination certificates. But photo ID existed well before the epidemic and it continues to be a tool of civic management to this day. Before being granted access to banks, bars, movies, sports events, borders, medical files, schools, even in some cases, food, people are being required to show ID and/or consent to a facial recognition scan. According to a recent study, 7 out of 10 of the world’s governments use such measures on a “large-scale basis.” Moreover, few national privacy safeguards exist to prevent “entire databases of citizen information” to be harvested, aggregated and sold on unregulated markets.

Was identification and identity validation the only intended purpose of the photo ID? By connecting the ID to the history of photography, particularly those chapters in the history of photography history that involve documenting and studying people’s faces, this project aims to demonstrate the potentialities of the photo ID beyond surveillance.

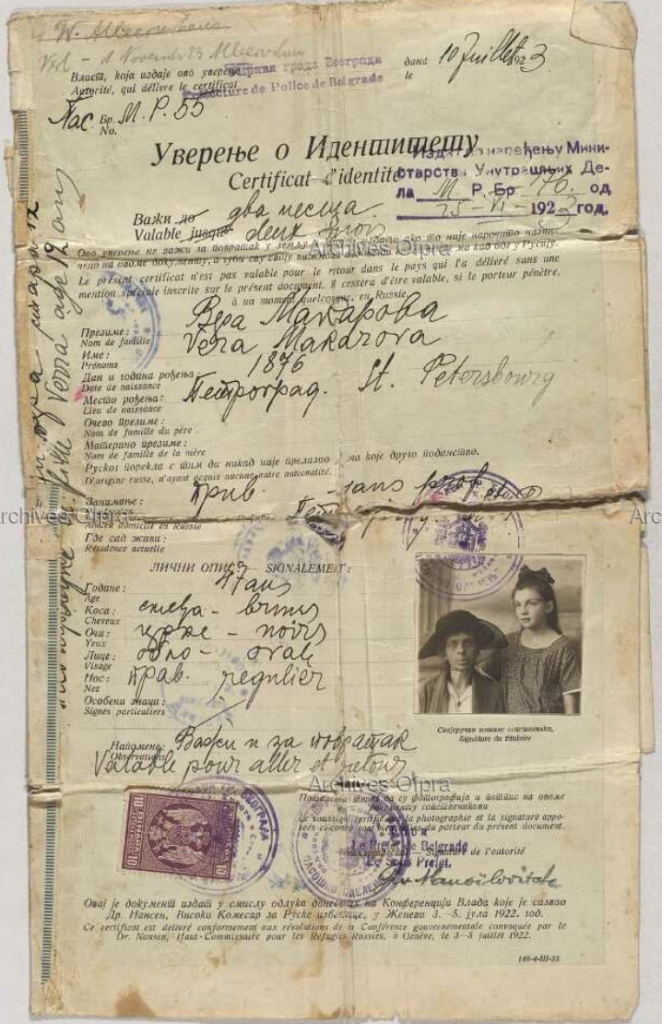

First appearing on documents recording the existence of individuals in the early 20th century, the photograph had uses in addition to providing individuals with a means of certifying their identity. It also placed the individual in relation to others through acts of visual comparison, epistemic analysis and speculative conjecture. At different points in time and space, the ID can be demonstrated to have treated the subject on its photograph as a scientist would a specimen, a detective a suspect, an artist their sitter, a clairvoyant a cup of tea leaves, a prosecutor their evidence, an attorney their defendant. This multiplicity of intention within the historic photo ID is partially on account of the ID photograph’s reproducibility. While we connect identity photography to individuals and individual identities, its production involved a universally standardized process that treated each sitter interchangeably, as when, for instance, the first unmanned photo booth was patented in the 1920s. Although its designation as a photography of “identity” could associate it with the artistic genre of photographic likeness called the portrait, the identity photograph is actually anything but a portrait. It is phantasmagoric in its ability to appear in multiple and often unexpected spaces simultaneously. A message without a code, the identity photograph has supported a range of decision-making and judgment passed on civilians, often without their knowledge. Through to this day, this situation of virtual address to the image, the expectation that, in the absence of an individual, their photograph will be able to represent and argue for their interests, constitutes the photo ID’s greatest leverage over the individual civilians’ rights and freedoms.

Is treating photographed faces as a unique identifier or a barcode the best use of photo IDs? Hacktivists have warned that automated visual recognition processing systems also use algorithms that are biased toward majoritarian populations (“coded bias“) and thereby already produce errors that “increase inequality and threaten democracy,” concerns that have been made known to regulatory bodies such as the European Parliament.

This project aims to show that, in addition to deriving knowledge of the human, identity photography has also helped negotiate, instantiate and hold nation-states accountable to the processes of civic protections, refugee rights, human rights, social justice movements and international solidarity. By creating a space of political relations that are not mediated exclusively by the ruling power of the state, a civil political space, much like a civil contract (Azoulay), the identity photograph has shown itself to potentially transcend military-territorial frameworks and provide individuals recourse to institutions, networks and communities that safeguard justice, citizenship and democracy.